British Cannon Design 1600 - 1800

Ordnance at the end of the Elizabethan Age

During the reign of Elizabeth I of England, gun design had been gradually improved through trial-and-error and scientific experiment. By 1600, gun design had achieved most of the developments necessary for the guns to perform their role in warfare.

Gun design was centrally controlled by the Board of Ordnance whose principal office holder was the Surveyor of the Ordnance. Standard examples of shot were kept by the Ordnance Office, the ability of new guns to fire these standard sizes determined the gun's category. Each category had its own name. An inventory of the Royal Ordnance taken in 1637 reveals that were 8 principal categories of gun in the armoury: Cannon, Demi Cannon, Culverins, Demi Culverins, Sakers, Minions, Falcons and Bases. Within these categories were various sub-categories; "legitimate" or "indenture", which meant the gun was made with the standard metal thickness (10 calibre circumference at the touch hole[1]), "reinforced", which had a greater metal thickness, "bastard" types which were often of lighter weight gun and took a lesser powder charge[2]. There were also "cutts" referring to guns with shorter barrel length.

The cost of heavy guns was high and captured guns and older types were reused until they were no longer serviceable, resulting in considerable variation in specifications of guns in service.

17th Century cannon styles

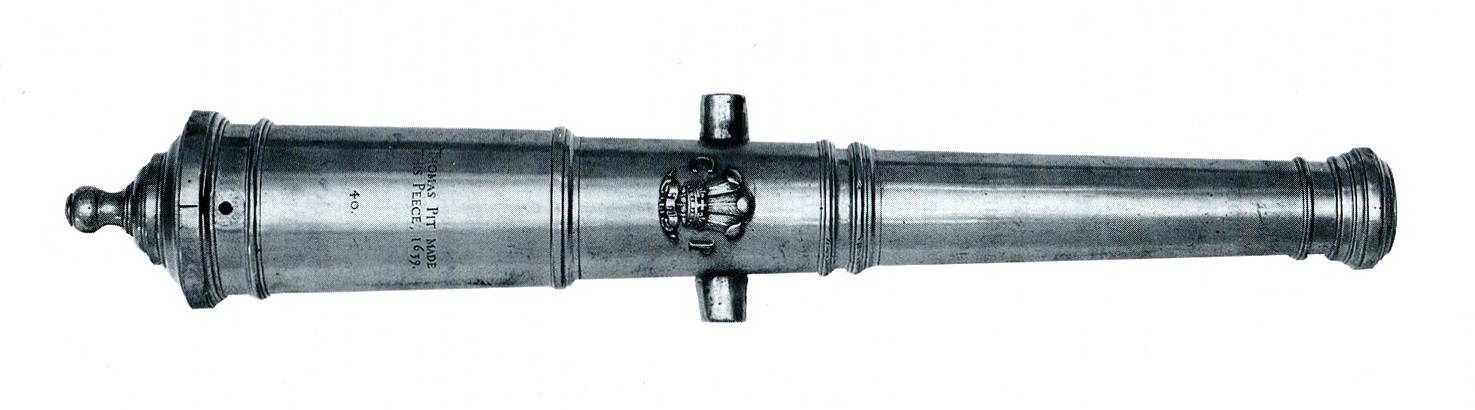

During the 1600s orders for guns specified calibre, weight and length, but left the rest up to the skill and discretion of the gunfounder. The designs were distinctive to the foundry. Fig 1 shows a mid 17th century cast bronze gun made by John Browne for the then Prince Charles, later King Charles I. Fig 2 shows a bronze gun made by Thomas Pitt for King Charles. The different breech styles, the thickness and position of the reinforces are quite different and specific to each gunfounder.

Figure 1. 17th century Bronze Cannon cast by John Browne. source: Royal Armoury.

Figure 2. 17th century Bronze Cannon cast by Thomas Pitt. source: Royal Armoury.

17th Century cannon calibre

Many different values are quoted for the calibre of the various gun types. A gun might have bore of 3¼", 3½" or 3¾" and still be quoted as a Saker. The bore of guns made to fire the standard round shot could also vary considerably. A gun may need to be bored with a larger diameter in an effort to make a straight smooth bore, particularly so for cast iron guns. This resulted in a greater windage, the difference in diameter between shot and bore, than would be achieved with a bronze gun. The smoother the bore and the smaller the windage, the better the gun would perform.

Drakes

In the mid 1620's the biggest market for guns was the Navy, which preferred guns cast in "brass" because they were lighter than their cast-iron equivalents. The metal used was actually bronze but it was always referred to as brass.

The Navy commissioners were directed to investigate the possibility of light-weight iron pieces, perhaps with the intention of replacing the more expensive "brass" guns. Only the gunfounder, John Browne was willing to undertake the work. Six of these guns, known as Drakes, were tried and proofed by being fired with double the normal powder charge. So successful were Browne's guns, that in 1627 he received an order for 4 demi-cannon, 16 culverins and 120 demi-culverins, all to be cast iron drakes.

The key feature of the drake was the powder-chamber which tapering toward the breech[3]. This effectively created a thicker walled breech and a smaller powder chamber. The drake's restricted powder chamber meant that they used a smaller charge than normal guns of similar calibre and length. This may explain why they could safely withstand proofing despite being lighter than legitimate guns.

The term Drake became used to described various cannon. Drakes were usually lighter than ordinary guns of the same calibre and length. For instance, Culverin drakes with a length of 8 ft were approximately 13% lighter than culverins of the same length. However, this was not the case with the large guns, demi-cannon drakes weighed the same as ordinary demi-cannon[4].

Table 1, shows the types of new iron guns ordered by the Commonwealth Government between 1650 and 1653 and demonstrates the popularity of drakes and shows that they were no shorter than other guns of the same type.

| Type of gun | Numbers of guns for given length | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 ft | 7½ ft | 8 ft | 8½ ft | 9 ft | 9½ ft | 10 ft | 10½ ft | 11 ft | |

| Demi cannon | 22 | 25 | |||||||

| Demi cannon drake | 64 | 51 | 240 | 2 | |||||

| Culverin | 37 | 10 | 5 | 2 | |||||

| Culverin drake | 866 | 130 | 2 | 12 | 34 | 3 | |||

| Demi culverin | 76 | 57 | 114 | 4 | 4 | 14 | |||

| Demi culverin drake | 10 | 964 | 25 | 2 | 94 | ||||

| Saker | 66 | 2 | 4 | 4 | |||||

| Saker drake | 11 | 235 | |||||||

| Minion | |||||||||

| Minion drake | 6 | ||||||||

Table 1. Iron guns ordered by the Cromwell Government 1650-1653[4].

Prince Rupert patent

The first major improvement in ordnance design occurred after the second British-Dutch War of 1666-67. The Dutch Raid of 1667 prompted a rearmament programme. Prince Rupert was granted a patent on a process for annealing cast iron guns so that they could be machined as if they were wrought iron[5]. During the 1670s the gunfounder John Browne produced several guns by this process. The annealing did allow for much smoother, truer bore than the rough cast iron guns but the process was much more costly and production ceased.

Eighty years later these guns was still being cited as an example of good design and were probably the best designed smooth-bore guns ever produced in Britain, certainly considerably better than those produced during the 18th and 19th centuries. They were designed on the basis of 11 calibre (bore diameter) circumference at the touch hole diminishing to 7 calibre at the neck[1].

An example of a Rupertino cannon exists in the Royal Armoury. It has a bore of 7.20 inches. Assuming that it was designed for 7 inch round shot, this represents a bore 36/35 times the shot diameter, windage of only 3%.

Design expertise is lost

After the installation of the Dutchman, William of Orange as king in 1689, many appointees to the Ordnance office were from the continent, led by the Duke of Schomberg, whom William appointed Master General of the Ordnance. The Board of Ordnance was thoroughly purged and the accumulated English design expertise lost. The same thing happened in 1714, when Queen Anne died and the German, George I took the throne. The last remnants of the good British gun design were lost, British artillery design became heavily influenced by French gun designs.

Borgard design

Albert Borgard was a Danish mercenary who joined the English Army in 1692. By which time he had been present at 11 battles and 12 sieges, and was one of the most experienced artillery and engineer officers in Europe. He was appointed an Ordnance engineer in 1698. As a still active artillery officer he served with distinction but was severely wounded and taken prisoner. On being exchanged he returned to England in 1712 and was appointed Chief Firemaster, in charge of the ammunition Laboratory[6].

In 1714, Brig-Gen. Michael Richards was appointed as Surveyor of Ordnance. Borgard was appointed as a divisional engineer under Richards, in 1715. In 1716 Borgard was tasked by the Board of Ordnance to oversee the standardization of artillery and gun carriages[7].

In fulfilling this task, Borgard was the first, and last, person to design a complete system of artillery. He dispensed with the naming of cannon as Culverin, Minion, Saker etc. and the guns became known by the weight of the round shot they fired. The round shot were standardized to the weights 4, 6, 9, 12, 18, 24, 32 and 42 pounds. These numbers were based on rounding to the nearest pound, the weight of the most common values of the round shot in use [see Cannonball page]. The designs were accepted by the Board of Ordnance in 1716.

Borgard's gun designs were not particularly successful, and few were produced in significant numbers.

Armstrong design

On Richards death in 1722, Colonel John Armstrong, who had replaced Richards as Chief Engineer in 1714, took over as Surveyor General of Ordnance. Armstrong immediately set about redesigning the Borgard system with modified designs in 1722 and 1724[1]. His aim was to lighten the guns. Unfortunately, this made them even more prone to failure. Over the next two decades the strength of gunpowder had increased, exacerbating the problem, heavier models were tried. They were shown to be inadequate during the early years of war with Spain (1739-1749) prompting another re-design in 1742.

Armstrong died in 1742, the new Surveyor General was Thomas Lascelles who oversaw redesigns in 1743 and partial redesign in 1744, which proved adequate for service during the remaining years of the war.

In 1750 Charles Frederick took over as Surveyor General. Frederick made some minor changes to the gun design in 1753. The "Seven Years" war with France began in 1756, the guns were again shown to be under strength. This resulted in a final redesign in 1760 which eventually proved successful and was adopted as the regulation design in 1764.

The success of the Armstrong-Frederick design of 1760 may be attributed to two factors other than Frederick's minor modifications. The first was the reduction, in 1764, of service gunpowder charge from ½ the shot weight to ⅓[8]. The second was the change in British gun-founding technique from casting hollow barrel guns and reaming them out to size, to casting solid barrels and drilling out the bore. This newer technique, begun in 1774 and mandated in 1776[10], produced far fewer flaws in the casting resulting in stronger barrels.

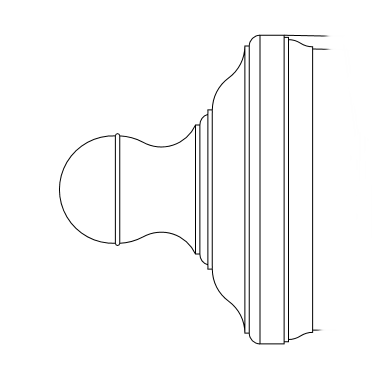

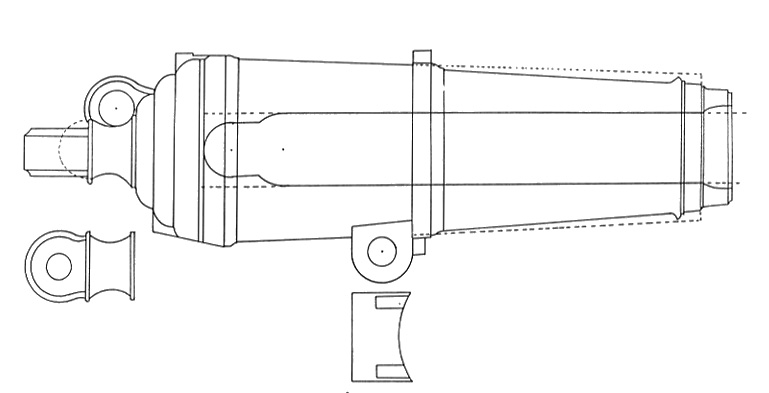

It was with these guns that the British fought the American War of Independence. Because the external features of the Armstrong pattern were largely retained across the many re-designs, these guns are generally known as Armstrong guns but more accurately its the Armstrong-Frederick pattern of 1760 which survive in large numbers today. They are most easily identified by the characteristic Armstrong cascable design shown in Fig 3. Fully detailed drawings of Armstrong pattern guns of all calibres and lengths are shown in the Armstrong pattern guns page.

Figure 3. Armstrong pattern cascable diagram 1760.

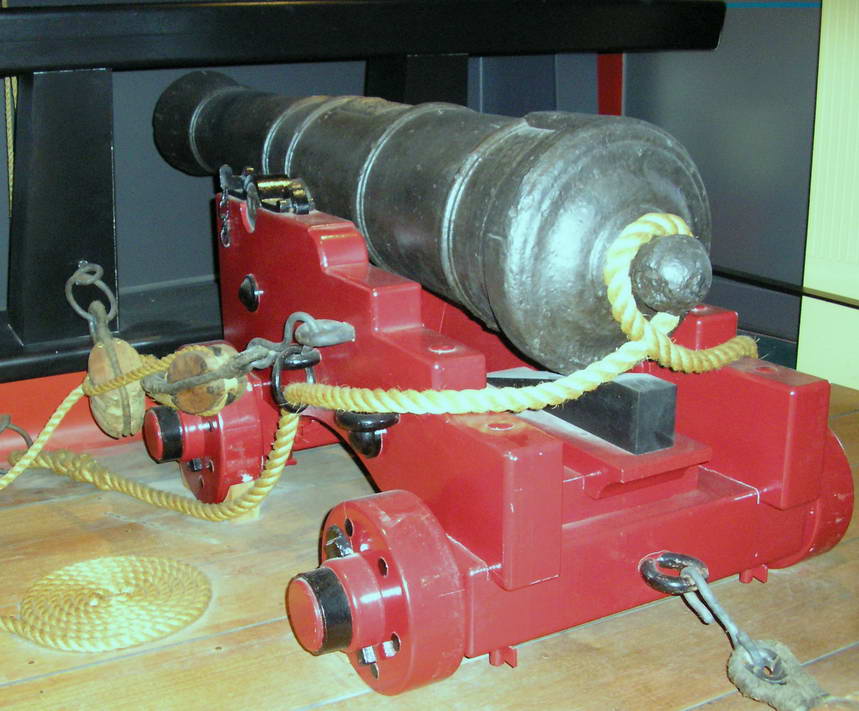

Figure 4 shows an example of the Armstrong pattern, a 4 pdr from Cook's HMS Endeavour.

Figure 4. Armstrong pattern 4 pounder, c1770.

Blomefield design

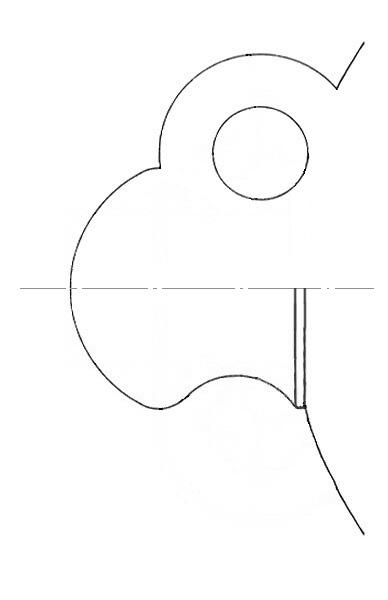

Thomas Blomefield became Inspector of Artillery, in 1780. Between 1782 and 1785 his department carried out a general reproof of ordnance, he rejected nearly half of them. In 1787 cast iron guns of Blomefield's own design were made. He made three significant alterations to the Armstrong design. Firstly, the breech was made more rounded, eliminating the prominent mouldings. Secondly, the first reinforce was made almost cylindrical, the second reinforce was strongly tapered and the chase strengthened. Thirdly, a ring was added to the cascable which allowed free movement of the breech ropes, used to restrict the gun's recoil aboard ship. This free movement allowed the gun to be trained at an angle to the side of the ship and still have effective recoil restraint. The characteristic Blomefield cascable design is shown in Fig 5.

Figure 5. Detail of Blomefield pattern cascable, showing breeching loop arrangement.

The guns represented an improvement in design, but did not solve the problem that they were unnecessarily heavy for their performance.

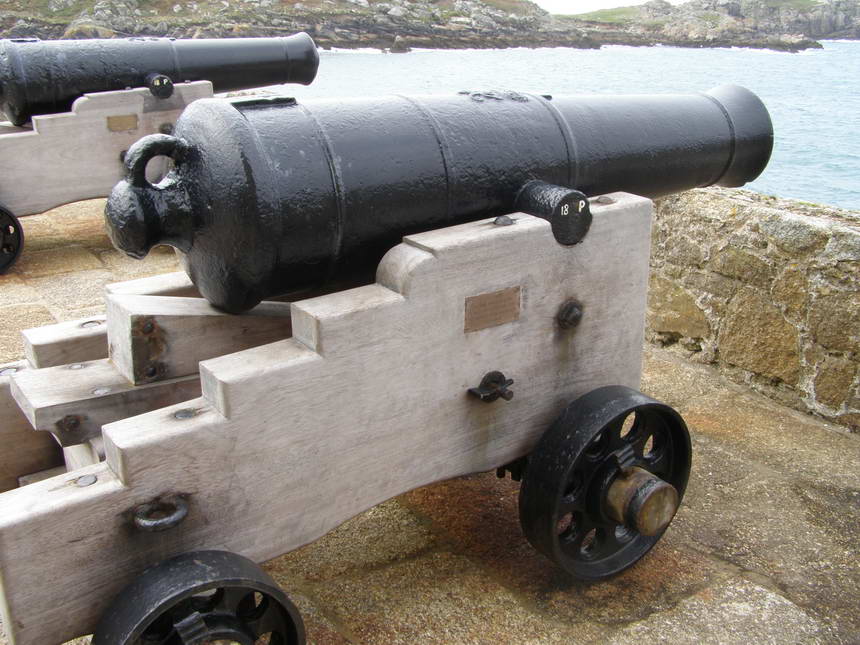

By 1792 gunfounders were mostly all using the "new pattern ordnance"[9]. By the early 1800s the Royal Navy had about 1000 ships with 30,000 guns, most cast since 1790. The Napoleonic Wars were fought and won with Blomefield guns and carronades. Fig 6 shows a Blomefield short pattern 18 pounder.

Figure 6. Blomefield pattern 18 pounder c1792. Showing the distinctive loop on the breech.

The Carronade

The most radical design change of the British gun design was the development of the carronade, A very short version of the standard gun. The carronade was largely developed by private enterprise toward the end of the 1770s, when naval tactics were changing from rigid "line of battle" actions to more close quarters combat. The carronade had a much shorter range than the ordinary gun but could be handled more easily in the close confines of a fighting ship.

The idea of the carronade was not new, in the early 1600s short barrelled guns in service were referred to as "cutts". These were initially made by cutting off the muzzle of a failed gun, but later they became a type of their own.

The early carronades were very short, about 18 inches. They were used during the American War of Independence. By 1795 the carronade was fully developed, and were typically 32 inches long, had a lower loop instead of trunnions and an elevating screw. The older designs were withdrawn from service. The carronade saw wide use during the Napoleonic wars to great effect[9].

Figure 7. Schematic drawing of late model carronade c1795[9].

Figure 8. Carronade late model c1795.

References:

1. A.B. Caruana "British Artillery Design", Royal Armouries Conference Proceedings 1

2. S. Bull "The Furie of the Ordnance", Boydell Press 2008

3. D. Blackmore Arms & Armour of the English Civil Wars, Royal Armouries 1990

4. G.M. Wilson "The Commonwealth Gun", Conference Proceedings 1986

5. S. Barter Bailey John Browne and Prince Rupert's guns, Royal Armouries 1987.

6. "Survey of London, Woolwich" Ch3 'The Royal Armoury', Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL

7. J.A. Browne "England's Artillerymen", 1865

8. A.B. Caruana "The History of English Sea Ordnance", Volume II 1997.

9. B. Lavery "Carronades and Blomefield Guns", Royal Armouries Conference Proceedings 1

10. D. McConnell "British Smooth Bore Artillery", Minister of Supply Services Canada 1988.

by: